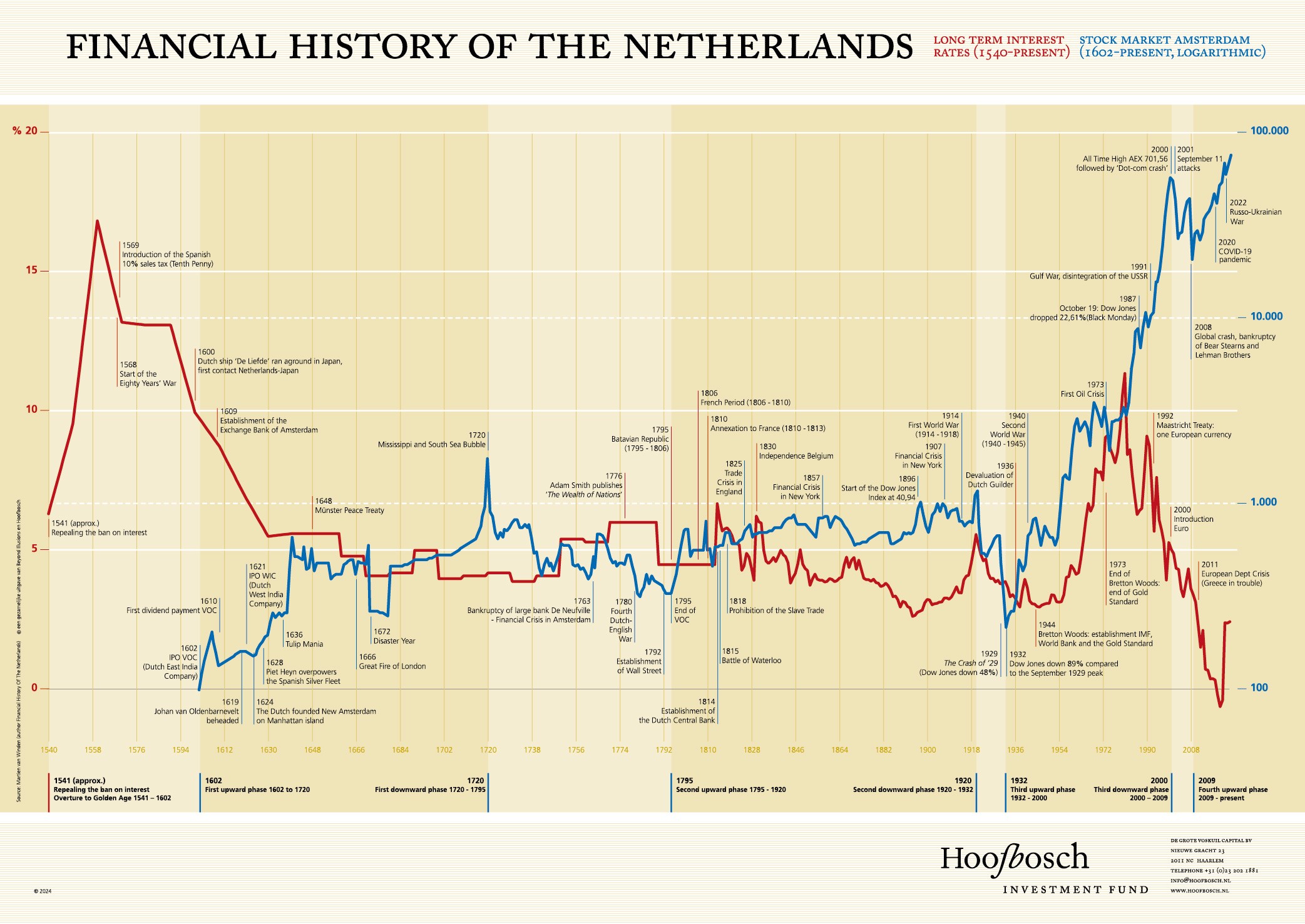

More about the interest poster

Interest Rate Chart

Working with Beyond Illusions, Hoofbosch Investment Fund has created an historical graphic overview of Dutch stock prices and Dutch interest rates in poster form. It captures Dutch interest rates starting in 1541 and stock prices starting in 1601 through end 2024.

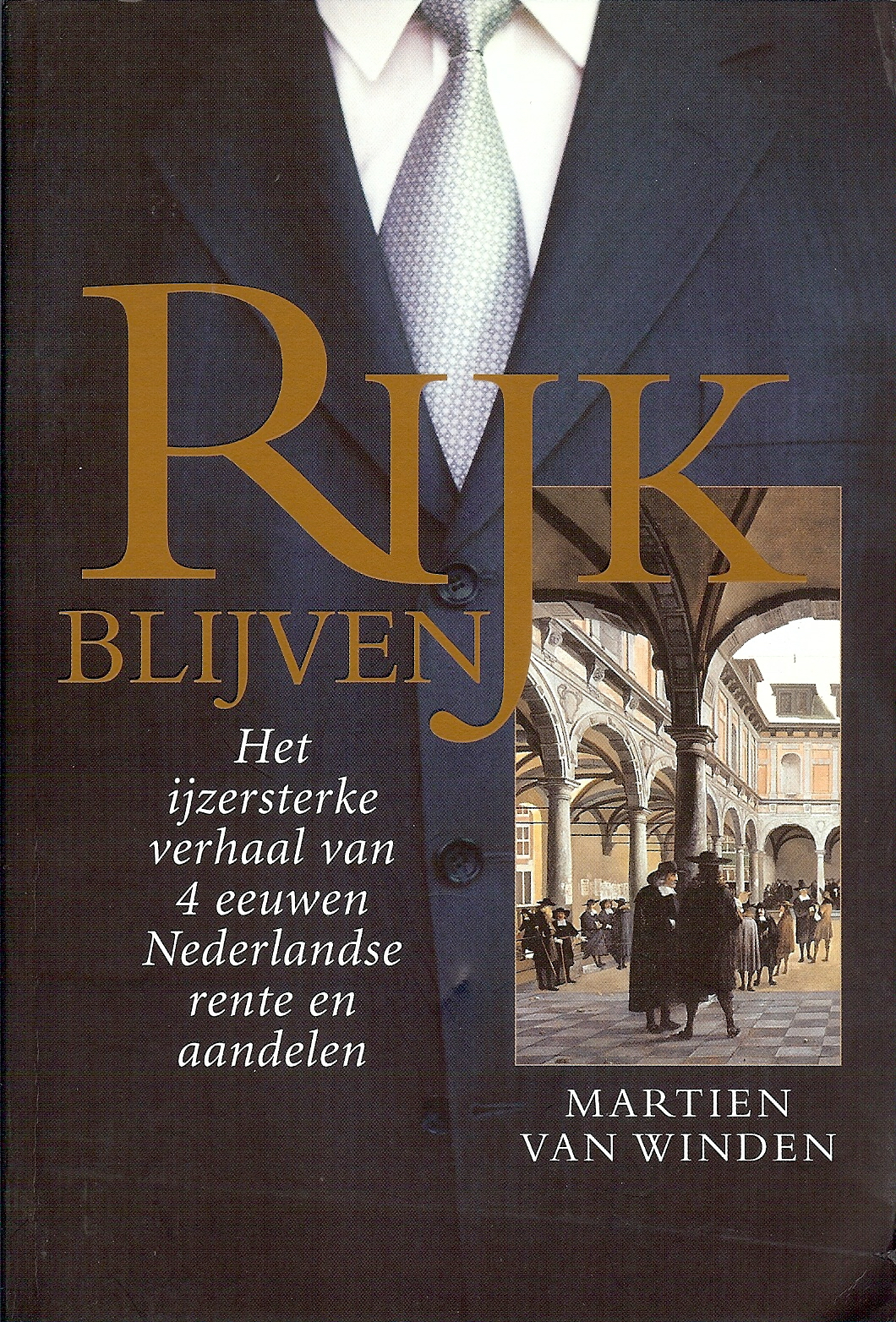

Books